Understand Lube ID Systems

Ken Bannister | August 11, 2017

Make sure you’re pumping the correct lubricant into your bearings.

Individuals, businesses, governmental agencies, nations, and other entities are obsessed with identification gathering and use of personal data these days. It seems we cannot move across a border, access money, make purchases, or enter a computer program or building without having first set up a user name and password arrangement or presenting credentials in the form of a license, passport, or some other type of government-issued ID card.

People have become a commodity who, under the guise of security, are being tracked and trended in everything we do. This allows countless ID “collectors” to perform analytics on our lifestyles and, among other things, leverage that information to tailor and market goods and services to us as individuals or demographic groups.

For ID collectors, premium identification information shows or describes what we look like, spells out our names, current addresses, ages or dates of birth, occupations, and, frequently, our likes and dislikes, depending on how much we have elected to share with the planet at large. If we were pieces of equipment, this information would be classified as “nameplate data.”

In general, equipment nameplate data is abundant and readily available for use—should we choose to find and use it. One would think, with all the personal data sharing to which we contribute that we would be exceedingly familiar with the various ID systems in plant environments. Sadly, this is rarely the case.

Equipment-nameplate data is valuable specification information printed or stamped on a plate, sticker, or tag attached to a machine, in a conspicuous place. At a minimum, the nameplate spells out the machine title/name, model, and serial number. In some cases, nameplates will contain much more detailed and relevant operations and maintenance data, such as operation-speed ranges, pressure settings, set-up details, spare-part numbers for consumable items, i.e., belts, chains, air/oil filters, and if we are lucky, the equipment’s lubricant-ID specification and fill rates. This information is usually more detailed in the machine’s operations and maintenance (O&M) manual, wherein all recommended lubricant brands, types, viscosities, and fill rates are noted.

In some instances, the original equipment manufacturer (OEM) will “nameplate” the lubricant and filter requirements on the lube reservoirs or pumps themselves, i.e., printing and attaching actual nameplates, stickers, or tags. We must seek out and review this essential data to set up best-practice lubrication programs, as well as to continue validating that correct lubricants are being used at fill or change-out time (to eliminate cross-contamination). We must also be aware that posted data could fail if an operation changes its lube supplier and another product is substituted for an original lubricant without adequately updating the ID information. That type of failure can lead to mistrust of all lubricant-identification labels.

Lubricant-ID control systems

Lubricant-ID-control mechanisms have been used for approximately 70 years. M.J. Harrison unveiled one of the most popular in a 1950 article titled “Color Codes,” published in the UK’s Scientific Lubrication Journal.

In his article, Harrison, an engineer with C.C. Wakefield & Co. (which later became Castrol), detailed a symbol/color-based control-system methodology to help unskilled workers perform “factory lubrication” in a consistent manner, with scientific precision. His approach was based on symbols to denote frequency of application, and colors to signify lubricant type. He further advocated the use of the colors on reservoirs and dedicated transfer equipment to diminish the chance of cross-contamination. Sound familiar?

Harrison initially promoted the use of three primary colors: red, blue, and yellow. Over time, as evidenced by commercially available lubricant-identification systems, we’ve become comfortable with the inclusion of green, orange, and purple.

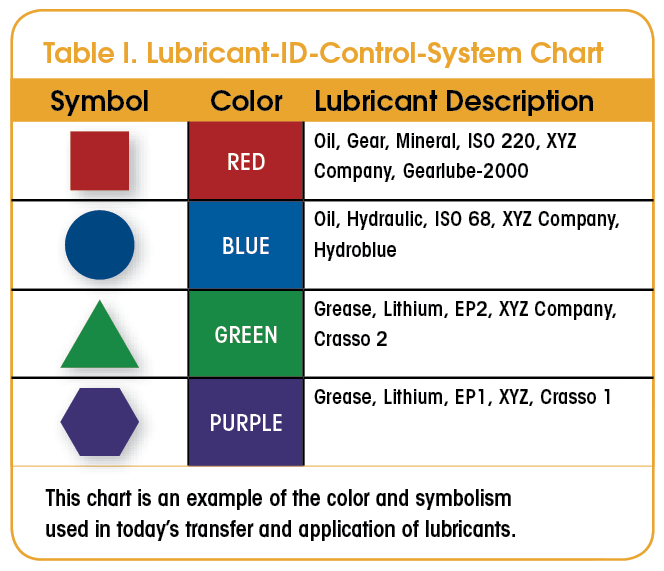

Table I shows the color and symbolism that’s used in today’s “modernized” transfer and application of lubricants. Figure 1 at the top of this page shows this type of color and symbolism on a customized label that can be attached to equipment and transfer containers.

Remember that, even with color-coding in place, an ID-control system can still fail when a lubricant is substituted and the specification on the machine and in the O&M manual isn’t updated to reflect, say, a yellow or red lubricant change from an X-brand specification to Y- brand specification product. Color-coded systems can also fail if personnel are color-blind. Since that can be a possibility in any plant, the lubricant ID should be accompanied by color within a control symbol and spelled out alongside the color/symbol on an ID nameplate, sticker, or tag located on the reservoir or at the lube-control point, or on the lubricant-ID-control-system chart (Table I) that’s given to all operators and maintainers and posted on or near the lubricated equipment.

Implementing a lubricant-ID control system

The following steps are required in setting up and maintaining a simple lubricant-ID control system:

- Work with your lubricant supplier to perform a lubricant-consolidation program to determine the minimum number of lubricants required for use on site.

- Catalogue and document all lubricant points and reservoirs by machine against the recommended lubricant-consolidation list.

- Develop a lubricant-ID control chart as depicted in Table I, designating a symbol and color for each recommended lubricant on the consolidation list. For clarity, use a noun/descriptor naming convention similar to the format used in the lubricant-description field of Table I.

- Print out individual lubricant ID nameplates, stickers, or tags (these are often supplied by the lubricant supplier; remove all old lube references from the machine; and attach the new ID information to reservoirs or relevant pump points.

- Update all preventative-maintenance (PM) job tasks with new lubricant descriptions.

- Update all relevant lubricant specifications in the O&M manual.

- Update the inventory-control system to close out old products and enter new lubricant product information.

- Update all equipment bills of materials (BOMs) to reflect only new lubricants.

- Update any previous symbol/color-code references to reflect the new ID control-system chart.

- Purge all old lubricant transfer containers and grease guns and replace with new dedicated, appropriately tagged color-coded transfer equipment and see-through grease guns to match the new lubricant-ID control system.

- Flush all old lubricant pumps using the oil supplier’s recommended flushing oil and procedure.

- Institute a change-notice requirement process to remove, replace, or add a lubricant in the plant, or to the ID control list.

- Train all plant personnel involved in the engineering, purchase, issue, storage, or application of lubricants on the new lubricant-ID control system.

(NOTE: If sufficient space isn’t available for a comprehensive ID nameplate, sticker, or tag, a bar code, RFID, or QR code readable from a cell phone can be used.)

A lubricant-ID control system is a way to mistake-proof your application of lubricants. This form of mistake proofing is a crucial part of a best-practice lubrication program.

Lubricant ID issues are among the many topics covered in Ken Bannister’s most recent book Practical Lubrication for Industrial Facilities–3rd edition (2016, Fairmont Press, Lilburn, GA), co-written with Heinz Bloch. Bannister can be reached at kbannister@engtechindustries.com or by telephone at 519-469-9173.

“Lubrication Storage and Handling Tips for World-Class Contamination Control”

“Purposefully Designed Lubricant Transfer Containers Save Bearings”

View Comments